Overview

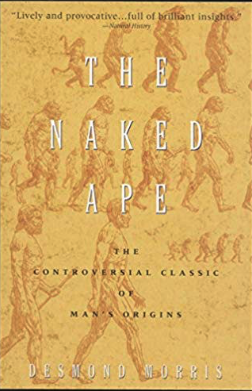

Prior to taking a short holiday vacation back to the states, I was scrambling to finish a book that my Dad gifted to me last spring. The book is called The Naked Ape and it was written in 1967 by Desmond Morris, an English zoologist. It was a fascinating read and one that made we wonder why it isn’t included on more collegiate or even primary school reading lists.

In this review, I’m going to take a chapter-by-chapter approach to break down The Naked Ape so that you have a better understanding of the central arguments Morris presents throughout the book. For each chapter, I’ll also include a quote or two that embody those arguments.

Chapter 1: Origins

In his opening chapter, Morris seeks to explain how applying the typical biological examination used for animal species in zoological studies is relevant when applied to what he calls ‘the human animal.’ He explains that, from his viewpoint, science has largely ignored the biological development of the human animal (at least up to that point) and that ignorance has stemmed from us incorrectly removing the human animal from the greater community of life.

He continues to detail the human animal’s evolution from foraging primate to carnivorous ‘hunting ape’. He points out that, “Killing is not, in fact, a basic part of the primate way of life,” and that “It is only a wise primate, like our hunting ape, that knows its father.”

The central argument of Chapter 1 is that, while the human animal largely owes his current place in the community of life to his/her intellectual development, this development is still very much in its infancy (in the grand scheme of history) and that much of our actions and interactions today are still influenced by our most basic biological necessities. He sums up this argument here:

“…there he stands, our vertical, hunting, weapon-toting, territorial, neotenous, brainy, Naked Ape, a primate by ancestry and a carnivore by adoption, ready to conquer the world. But he is a very new and experimental departure, and new models frequently have imperfections. For him the main troubles will stem from the fact that his culturally operated advances will race ahead of any further genetic ones. His genes will lag behind, and he will be constantly reminded that, for all his environment-moulding achievements, he is still at heart a very naked ape.”

Chapter 2: Sex

In Chapter 2, Morris dives into the sexual relationships of the human animal. To do so, he begins by explaining the common mode of sexual relationships among primates. In summary, Morris argues that primates don’t form ‘pair-bonds’ like we find common among humans. Instead, female primates may copulate with multiple males before becoming pregnant with young. Thus, it is virtually impossible for primates to know who the exact father of the offspring is.

As we evolved to become ‘hunting apes’, Morris suggests, there arose a greater need to form pair-bonds, which are more common among carnivorous animals. Morris suggests that the need for the formation of pair-bonds arose out of relatively newfound hunting behavior. There were certain factors unique to the hunting ape that drove it to become one of the few primate species that forms pair-bonds, but Morris central argument is that, evolutionarily, this is still a relatively new development. He sums this up here:

“Sexually the naked ape finds himself today in a somewhat confusing situation. As a primate he is pulled one way, as a carnivore by adoption he is pulled another, and as a member of an elaborate civilized community he is pulled yet another.”

One of the more poignant side-arguments that Morris presented in Chapter 2 dealt with population expansion. Despite the fact that he expressed this view more than 50 years ago, I found it to be quite relevant today. Morris concluded Chapter 2 with this statement:

“Thanks to medical science, surgery and hygiene, we have reached an incredible peak of breeding success. We have practiced death control and now we must balance it with birth control. It looks very much as though, during the next century or so, we are going to have to change our sexual ways at last. But if we do, it will not be because they failed, but because they succeeded too well.”

Chapter 3: Rearing

Morris’ third chapter was one of the most insightful of the entire book, from my perspective, and a must-read for anyone that has or is thinking about having kids. He begins by detailing the human child’s response to the heartbeat rhythm. He presents research that suggests children are powerfully stimulated by the sound of the mother’s heartbeat, which is why most mothers (regardless of whether they are left or right-hand dominant) carry children on their left side.

Morris also details the power of imitation among children. In other words, he presents scientific evidence that the old adage “do what I say and not what I do” is entirely ineffective. He suggests:

“An agitated mother cannot avoid signaling her agitation to her new-born infant. It signals back to her in the appropriate manner, demanding protection from the cause of the agitation. This only serves to increase the mother’s distress, which in turn increases the baby’s crying. Eventually the wretched infant cries itself sick and its physical pains are then added to the sum total of its already considerable misery. All that is necessary to break the vicious circle is for the mother to accept the situation and become calm herself.”

Building upon this argument, Morris details evidence that much of the imitative absorption that happens in our childhood remains with us throughout our entire lives. While we may attribute our actions and decisions to more recent stimuli, there is sufficient scientific evidence behind the reason why so many psychologists seek to understand a patient’s childhood when attempting to remedy what we view as more ‘current’ maladies. Morris makes his argument here:

“Much of what we do as adults is based on this imitative absorption during our childhood years. Frequently we imagine that we are behaving in a particular way because such behaviour accords with some abstract, lofty code of moral principles, when in reality all we are doing is obeying a deeply ingrained and long ‘forgotten’ set of purely imitative impressions. It is the unmodifiable obedience to these impressions (along with our carefully concealed instinctive urges) that makes it so hard for societies to change their customs and their ‘beliefs’. Even when faced with exciting, brilliantly rational new ideas, based on the application of pure, objective intelligence, the community will still cling to its old home-based habits and prejudices. This is the cross we have to bear if we are going to sail through our vital juvenile ‘blotting-paper’ phase of rapidly mopping up the accumulated experiences of previous generations. We are forced to take the biased opinions along with the valuable facts.”

In presenting a balancing act for us to aspire to as we move forward, Morris concludes Chapter 3 with this insightful statement:

“Lucky is the society that enjoys the gradual acquisition of a perfect balance between imitation and curiosity, between slavish, unthinking copying and progressive, rational experimentation.”

Chapter 4: Exploration

As you can tell, the end of Chapter 3 offers a perfect segway to a discussion on the importance of exploration in the context of human evolution. Morris suggests that the survival of the human animal, as well as our massive population explosion, may be attributed to our desire to explore and experiment. He details the major difference between what he calls ‘specialists’ and ‘non-specialists’ in the animal kingdom.

Specialists are those that have found a food source that is plentiful, reliable, and for which there is very little competition. For specialists, there is almost zero variety in their diets. “So long as the ant-eater has its ants and the koala bear its gum leaves, then they are well satisfied and the living is easy,” says Morris.

For non-specialists (which he also calls ‘opportunists’), “the going may always be tough, but the creature will be able to adapt rapidly to any quick-change act that the environment decides to put on. Take away a mongoose’s rats and mice and it will switch to eggs and snails. Take away a monkey’s fruits and nuts and it will switch to roots and shoots.”

In other words, the ability to consume a varied diet is key to the survival of the human animal. But Morris goes onto discuss how we arrived here, in the present day, with the ability to consume such a varied diet. He attributes this trait to our exploratory nature which, interestingly enough, tends to be snuffed out as we grow older. This, to me, was the central argument of Morris’ fourth chapter, and he sums it up very nicely here:

“As children grow older their exploratory tendencies sometimes reach alarming proportions and adults can be heard referring to ‘a group of youngsters behaving like wild animals.’ But the reverse is actually the case. If the adults took the trouble to study the way in which adult wild animals really do behave, they would find that they are the wild animals. They are the ones who are trying to limit exploration and who are selling out to the cosiness of sub-human conservativism. Luckily for the species, there are always enough adults who retain their juvenile inventiveness and curiosity and who enable populations to progress and expand.”

Chapter 5: Fighting

I’m sure that many of us wonder why so much fighting goes on in the world today. For his part, Morris gives two reasons why animals fight. The first is “to establish their dominance in a social hierarchy” and the second is “to establish their territorial rights over a particular piece of ground.” In examining the human animal, most fighting that we see among ourselves today can be attributed to one of these two factors. Even the most seemingly pointless night club brawl is driven by that biological urge to establish dominance in that particular social hierarchy.

Morris makes a clear statement toward the beginning of the chapter on the dangers of intra-specific aggression:

“If a species is to survive, it simply cannot afford to go around slaughtering its own kind. Intra-specific aggression has to be inhibited and controlled, and the more powerful and savage the prey-killing weapons of a particular species are, the stronger must be the inhibitions about using them to settle disputes with rivals. This is the ‘law of the jungle’ where territorial and hierarchy disagreements are concerned. Those species that failed to obey this law have long since become extinct.”

Interestingly, Morris digresses to a critique of religion in this chapter. Considering the amount of historical violence that has occurred in the name of religious conquest, I suppose it is not all too surprising. What did shock me, however, was this suggestion:

“Religion has also given rise to a great deal of unnecessary suffering and misery, wherever it has become over-formalized in its application, and whenever the professional ‘assistant’s of the god figures have been unable to resist the temptation to borrow a little of his power and use it themselves. But despite its chequered history it is a feature of our social life that we cannot do without. Whenever it becomes unacceptable, it is quietly, or sometimes violently, rejected, but in no time at all it is back again in a new form, carefully disguised perhaps, but containing all the same old basic elements. We simply have to ‘believe in something’. Only a common belief will cement us together and keep us under control.”

He goes on to add a suggestion for beliefs that will serve us:

“As a species we are a predominantly intelligent and exploratory animal, and beliefs harnessed to this fact will be the most beneficial for us.”

Chapter 6: Feeding

Morris begins Chapter 6 with a discussion on how ‘work’ has replaced ‘the hunt’ in modern society. Despite the fact that many modern males don’t regularly kill and prepare their own food, he points out, ‘work’ in modern culture has many of the same characteristics as ‘the hunt’. These include our daily trips from home to the ‘hunting’ grounds, the need to take risks and plan strategies, and the predominance in the workplace of male-to-male interaction.

(This is one of the areas in which one is reminded that Morris published this book more than 50 years ago. Things have changed in the modern workplace but, as Morris states, many modern workers or “pseudo-hunters” still talk of “making a killing in the City.”)

Some of the more intriguing insights in Chapter 6 were centered on our attraction to certain types of foods. Morris suggests that it is our primate heritage that leads us to seek sweet tastes at the conclusion of an otherwise savory meal. He gives further detail on this biological urge here:

“…there is one aspect of our true tasting that requires special comment, and that is our undeniably prevalent ‘sweet-tooth’. This is something alien to the true carnivore, but typically primate-like. As the natural food of primates becomes riper and more suitable for consumption, it usually becomes sweeter, and monkeys and apes have a strong reaction to anything that is strongly endowed with this taste. Like other primates, we find it hard to resist ‘sweets’. Our ape ancestry expresses itself, despite our strong meat-eating tendency, in the seeking out of specially sweetened substances. We favour this basic taste more than the others. We have ‘sweet shops’, but no ‘sour shops’. Typically, when eating a full-scale meal, we end the often complex sequence of flavours with some sweet substance, so that this is the taste that lingers on afterwards. More significantly when we occasionally take small, inter-meal snacks (and therefore revert, to an ancient, primate scatter-feeding pattern), we nearly always choose primate-sweet food objects, such as candy, chocolate, ice-cream, or sugared drinks.

So powerful is this tendency that it can lead us into difficulties. The point is that there are two elements in a food object that make it attractive to us: its nutritive value and its palatability. In nature, these two factors go hand in hand, but in artificially produced foodstuffs they can be separated, and this can be dangerous. Food objects that are nutritionally almost worthless can be made powerfully attractive simply by adding a large amount of artificial sweetener. If they appeal to our old primate weakness by tasting ‘super-sweet’, we will lap them up and so stuff ourselves with them that we have little room left for anything else: thus the balance of our diet can be upset. This applies especially in the case of growing children. In an earlier chapter I mentioned recent research which has shown that the preference for sweet and fruity odours falls off dramatically at puberty, when there is a shift in favour of flowery, oily, and musky odours. The juvenile weakness for sweetness can be easily exploited, and frequently is.”

While this statement helps us understand our tendency towards sweets, as well as how that tendency can be exploited to our detriment, I found Morris’ final statements of Chapter 6 to be most poignant to modern day food production. He speaks of the evolution from the early days of ‘mixed farming’ (pre-Agricultural Revolution) to today’s systems of widespread animal domestication and mono-crop cultivation. He suggests that these two tendencies evolved hand-in-hand, but that their continued proliferation could have serious consequences for the health of our population:

“With advancing crop-cultivation techniques and the concentration on a very few staple cereals, a kind of low-grade efficiency has proliferated in certain cultures. The large-scale agricultural operations have permitted the growth of big populations, but their dependency on a few basic cereals has led to serious malnutrition. Such people may breed in large numbers, but they produce poor physical specimens. They survive, but only just. In the same way that abuse of culturally developed weapons can lead to aggressive disaster, abuse of culturally developed feeding techniques can lead to nutritional disaster. Societies that have lost the essential food balance in this way may be able to survive, but they will have to overcome the widespread ill-effects of deficiencies in protein, minerals and vitamins if they are to progress and develop qualitatively. In all the healthiest and most go-ahead societies today, the meat-and-plant diet balance is well maintained and, despite the dramatic changes that have occurred in the methods of obtaining the nutritional supplies, the progressive naked ape of today is still feeding on much the same basic diet as his ancient hunting ancestors. Once again, the transformation is more apparent than real.”

Chapter 7: Comfort

In Chapter 7, Morris discussed how certain forms of communal comforts, such as the regular grooming that is seen in primates, are exhibited in modern culture of the human animal. He discussed the adoption of a habit he refers to as grooming talk, which are those subjects we feel most comfortable broaching in a new social setting, or during introductions and conclusions of social gatherings (i.e. weather, the latest movies, entertainment news, etc).

Morris argues that grooming talk sets the stage for more in-depth conversations, but that it is essential to put everyone at ease before those more topical conversations can take place. In other words, it could be quite awkward if we began a completely new social interaction with a direct question about someone’s political or religious views.

In addition, Morris uses Chapter 7 to discuss the psychological aspects of illness. He suggests that some of our more common, ‘minor’ illnesses may actually be attributed to our need for comfort rather than a truly physical reaction to bacteria or virus. Morris summarizes his viewpoint here:

“An ailment that is severe enough to put us helplessly to bed, therefore, has the great advantage of recreating for us all the comforting attention of our secure infancy. We may think we are taking a strong dose of medicine, but in reality it is a strong dose of security that we need and that cures us.”

Morris goes on to point out that we are capable of prolonging illness in others by demonstrating a stifling need to provide care:

“Some individuals have such a great need to care for others that they may actively promote and prolong sickness in a companion in order to be able to express their grooming urges more fully. This can produce a vicious circle, with the groomer-groomee situation becoming exaggerated out of all proportion to the extent where a chronic invalid demanding (and getting) constant attention is created.”

Chapter 8: Animals

To bring our thoughts back to some of his initial arguments about our false view of humans being separate from the natural world, Morris’ final chapter deals with our interactions with our species in the animal kingdom. He makes arguments that our “symbiotic” relationships with other animals are actually very rarely mutually beneficial. In most cases, he argues, the other animal is exploited, “but in exchange for the exploitation we feed and care for them. It is a biased symbiosis because we are in control of the situation and our animal partners usually have little or no choice in the matter.”

From a purely scientific standpoint, Morris goes on to make a case for animal conservation. In other words, he argues that we have a duty to promote diversity in the community of life, if for no other reason than for our own curiosity:

“If we are to continue to enjoy the rich complexities of the animal world and to use wild animals as objects of scientific and aesthetic exploration, we must give them a helping hand. If we allow them to vanish, we shall have simplified our environment in a most unfortunate way. Being an intensely investigatory species, we can ill afford to lose such a valuable source of material.”

In this chapter, he also details some very intriguing studies among children that provide evidence for why we prefer certain animal species to others. It appears our aversion to snakes may very well be traced to our ancient primate heritage (snakes being one of the other tree-dwelling species capable of causing harm to most primate species). These studies also show that animals with similarly ‘human’ characteristics are preferred to those with which we struggle to identify.

Because of this natural biological attraction or aversion to certain animals over others, Morris makes this statement near the end of the chapter:

“As I have stressed throughout this book, we are, despite all our great technological advances, still very much a simple biological phenomenon. Despite our grandiose ideas and our lofty self-conceits, we are still humble animals, subject to all the basic laws of animal behaviour.”

Closing Thoughts and Final Opinion

In spite of an honest effort to provide an in-depth look at Desmond Morris’ The Naked Ape, I feel that this review has only just scratched the surface. Each chapter was full of insights and scientific evidence for why we find ourselves in this current position, why we do what we do, and what governs our daily interactions. I can say with certainty that I look at social settings, the current events of the world, and my own decision-making processes through entire new lenses now that I’ve finished this book.

In closing, I’d like to leave this review with Morris’ closing statement. Although I don’t 100% agree with the doomsday proclamation he makes here, I do think healthy consideration of our place within the community of life (rather than as rulers of that community), is in order if we wish to sustain healthy human existence on this planet:

“We must somehow improve in quality rather than in sheer quantity. If we do this, we can continue to progress technologically in a dramatic and exciting way without denying our evolutionary inheritance. If we do not, then our suppressed biological urges will build up and up until the dam bursts and the whole of our elaborate existence is swept away in the flood.”

Explore The Naked Ape!

While I hope you’ve enjoyed this summary of my most important takeaways from each chapter of Desmond Morris’ The Naked Ape, I want to stress that there is really no substitute for sitting down and digesting the entire book on your time. If you do choose to purchase The Naked Ape after reading this review, I’d love to know how the book speaks to you!

Also, I’d love to hear what other types of books or authors you’d like to see reviewed on this site. I’m always looking for new opportunities to read and review. My only regret is that my reading list tends to grow much faster than I’m able to check items off of it, so if you do leave me a suggestion, I appreciate your patience as I dive into the many books on my shelves!

Please leave a comment below if you are inspired, perplexed, saddened, or angered by any of the ideas presented above. I welcome any and all comments and will do my best to respond hastily. I’d also encourage you to share this with others if you found it particularly insightful or helpful. Be sure to tag @ballisterwriting on Facebook or Instagram if you do!

Happy Reading!

Tucker Ballister

Hello there thanks for this review on this book. I must commend your effort in putting up a few things on the book. Just last year I was privileged to read this book. My mom introduced it to me actually and after going through some pages I began to grow interest for it until I finished the whole book. I must say it was educative and broadened my understanding.

Hey Philebur!

It sounds like we share a similar story, as this book was actually a gift to me from my father. He read it back when he was around my age, but I feel like the lessons it holds are still so applicable to our lives today!

If you could identify one thing, what was your biggest takeaway from this book?!

I honestly haven’t read this work but I highly recommend the human animals.

In part of “The Human animals” author, the famous zoologist, is coming from the fact that even a human being is an animal that is unlike any other animal species in many of its properties. His claim is based on the study of men and animals. Through various forms of human behavior, you get insight into different actions of people, in shapes and meanings of their customs, habits, activities. The biological portrait of mankind shows that all human beings, regardless of the astonishing cultural differences, share almost the exact genetic heritage.

Anyway, thanks for the contents of the site.

Thank you for sharing your experience with “The Human Animals”!

I too found the idea of breaking down human behavior from a purely biological perspective very insightful!

Because of the band Brutal Truth i have read this book!

Oh yeah?! I’ll have to look them up. What did you think of the book?

Hi Tucker – I had not heard of this book, The Naked Ape, but it sounds like an interesting read. I appreciate your summary of each chapter to get a bit of insight into what the book is about. And I agree that we as the human animal should not feel that we are the absolute rulers.

Thanks for this information.

Michele

Glad you enjoyed it Michele! It was a very insightful read and my summary only just scratched the surface on the ideas it contained. I highly recommend getting your hands on it if you can!

Wow what an amazing read!!

It is amazing how far the human animal has come. It’s certainly going to be interesting in the upcoming centuries I think everyone is aware that things are rapidly changing and nobody knows quite how quick or what the consequences will be.

This truly is amazing to read. It’s fascinating how females used to just mate with different males so they didn’t know who the father was and how this changed!

Thanks so much for sharing

Mike

Yes Mike! That insight you picked out is just one of so many in Morris’ book. It was really interesting to read this just before I read The Story of B (my next review), as the two books tied together very closely and the second only built on some of the ideas introduced in the first. I highly recommend both!

Great and interesting book. Kudos to you for coming up with a detailed review and summary of Desmond Morris mind blowing book. The naked ape according to your summary explains in clear term man evolutionary trend and history. I agree with the chapter 2 majorly, The pair bond syndrome is a common one among humans till date. I will try to get a copy of this biological book.

Thanks Clement! I would love to hear from you after you read it, and if you’re looking for a great follow up that builds on some of the concepts introduced in The Naked Ape, be sure to check out Daniel Quinn’s The Story of B too!